9 things you didn’t know about Georgian wine

TBC Capital’s recent report Heritage of Splendor delivers a sweeping overview of the Georgian wine industry: from the difficulties faced by large-scale production to changing consumer habits and export trends.

Investor.ge sat down with TBC Capital’s head of research Tornike Kordzaia to take apart some of the most curious and surprising finds.

1. Wine rush

There was a rush to get into the wine biz in 2018 – 2019, TBC Capital’s report shows, with Georgia experiencing a jump in newly registered wine producers, increasing from 337 in 2018 to already 420 in 2019 H1.

The end of the state grape subsidies program at the end of 2018 may have played something of a role in this, as many wine growers and makers may have registered and formalized their production to benefit from the final throes of the program.

Another contributing factor were regulations introduced in 2016, which established mandatory quality controls and obliged wine producers hoping to export abroad to register their companies and submit samples for laboratory testing. Up until 2016 it was easier to get unverified products to market, while recent restrictions have made that harder.

Coming into the formal sector also has the added benefit of allowing wineries to add themselves to Georgia’s wine routes, which in turn attracts more tourists.

2. Vineyard consolidation picking up steam

The relatively small amount of land suitable for viticulture in Georgia has always framed the question of the wine industry’s priorities, and whether the volume of wine production will remain low.

TBC Capital thinks this issue is moving towards resolution, as smaller, private land plots are being consolidated into larger, formal production companies and away from household production. This is necessary not only for growth, but also to ensure standardization in taste and production.

However, one question remains as to what effect this will have on rural economies and livelihoods.

TBC Capital’s Tornike Kordzaia says this is unlikely to have serious consequences:

“Basically, almost half the population lives in the countryside, where the contribution to the economy is way less overall.

There is a great mismatch in the distribution of labor and productivity and urbanization levels will likely pick up with time.

As this happens, people will go into more productive industries and switch to the demand side of the value chain or become suppliers for formal production.

Natural demographic processes will support this process, not antagonize it.”

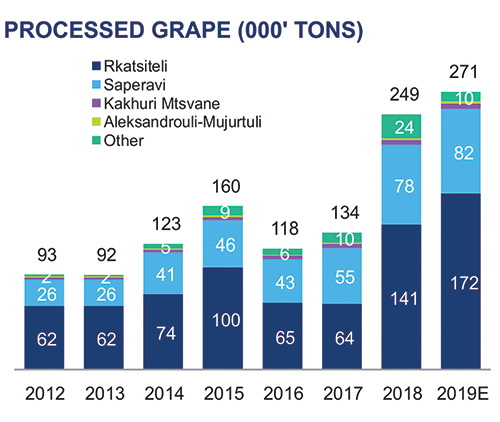

3. Two grapes to rule them all

While Georgia has over 500 varieties of grapes, just two of them account for 93% of all grape production in the country – Saperavi and Rkatsiteli. While many may associate Georgia with the ubiquitous Saperavi, it’s actually Rkatsiteli that makes for the overwhelming majority of wine production, with a 63% share of total grape production in the country.

TBC Capital’s Kordzaia comments:

“The first reason is that Rkatsiteli and Saperavi were both chosen for their weather resistant properties and high yields in Soviet times, so in part this is an issue of a remaining legacy. Other reasons include that Rkatsiteli and white wines are the drink of choice at supras, weddings and other large social gatherings, where the pace of drinking is quicker, and for that you need a wine that’s cheap to produce and easy to source.

“One other reason is that Georgian spirits, such as chacha and brandy, often use Rkatsiteli and its remains in their production, and it uses a lot: for every volume of Rkatsiteli wine produced, it can be used to make only around 7% of of the same volume of spirits.

However, TBC Capital expects a shift in production patterns – first because subsidies for Rkatsiteli production ended in 2018, which will shift attention elsewhere, and second because drinking culture is slowly moving away from quantity and drinking wine in large volumes, as consumers learn to enjoy finer wines in smaller quantities.

“What’s interesting is that export data show an almost flipped picture”, Kordzaia notes, pointing out that in 2019, 77% of wine exports by value were comprised of red wines, while whites made for just 21%.”

4. Rtveli harvest on two-year streak

Rtveli [grape harvest] yields in 2019 broke 30-year record highs for the second time in a row in 2019, with an estimated total of 282,000 tonnes of grapes processed in 2019, with largely good weather to thank.

However, as climate change progresses and vineyards experience less precipitation, grape growers are beginning to talk about the need to move to higher altitudes.

Kakheti remains the country’s main grape grower, responsible for the production of 72% of the Rtveli 2019 harvest, followed by Imereti (12%) and Shida Kartli (6%).

5. Coming out of the shadows

The share of household and shadow production of wine has been steadily decreasing since the early 2000s; in 2019, this pattern continued and even picked up pace, with formal production accounting for close to 88% of production value, while informal production made for just 9%.

TBC Capital reports that increased consumer purchasing power has led to local demand shifting towards better quality and standardization, and away from homemade wines.

For comparison, back in 2005 homemade wine accounted for more than 70% of production, and remained high during the years of the Russian embargo between 2007-2013.

6. Russia – again

To much of the sector’s chagrin, it’s difficult to talk about Georgian wine without talking about Russia. Currently about 60% of Georgian wine exports go to Russia, and despite talk of diversification, the market share of exports to the Russian Federation continues to rise.

The Russian market for wine remains attractive, given that there is no footwork needed to introduce Georgian wine to the Russian market, and the shipment of goods is cheap and the procedure simple.

However, Kordzaia says, TBC Capital’s analysis shows that this puts the market at risk: 30-40% and higher dependence on a single buyer country poses serious profitability and insolvency risks. Currently, many major winemakers in Georgia export as much as 50-60 percent of their product to Russia.

7. Fruitful returns

Despite the risks faced by the industry, the wine business remains incredibly fruitful with IRRs ranging between 14 – 18% and project payback period standing between eight to 10 years. TBC Capital estimates that initial investment per hectare of grape production on an industrialized scale ranges between 21,000-40,000 USD, depending on the variety of grape. PDO wines and plots located in microzones are the costliest.

8. Georgians drink less than you thought

One of the most surprising discoveries in the TBC Capital report: domestic consumption of wine is actually decreasing.

“This is seemingly due to a shift in drinking habits, where supras are becoming less the venue for drinking; instead, consumers are moving to bars, where the culture is less to guzzle, and more to sip and enjoy.” Not only is domestic consumption down, it is perhaps even more curious that it is far below the level of a number of European countries.

“This can partially be attributed to the levels of tourism in these countries, which going forward will be one of the main drivers of consumption in Georgia itself as well”, TBC Capital’s Kordzaia says.

9. Exports by wine type reflect opposite image of production

While white wine might make for the bulk of production in Georgia, red wine’s account for 77% of wine exports, and white wines account for just 21%. The breakdown of exports of wine by type for 2019 was: Alaznis Veli (28%), Kindzmarauli (22%), Saperavi (17%), Mukuzani (7%), Pirosmani (4%), Tsinandali (4%), Rkatsiteli (3%), Khvantchkara (3%), other (3%).

Russia and China import predominantly red wines from Georgia, with their share of imported Georgian white wines standing only at 10% and 3%. The EU’s imports are more balanced, with 69% of Georgian wine imports being reds, and 28% whites.

____________________________ ADVERTISEMENT ____________________________