Agro-exports to the EU: overcoming key barriers

Limited volumes, as well as specific barriers in transport and logistics, constrain the growth of agro-exports to the EU. Agricultural specialist Hans Gutbrod proposes four measures that could improve export prospects.

Production volumes, as well as barriers in transport and logistics, play a key role in constraining agro-food exports from Georgia to the European Union, according to a recent study of the German Economic Team.

These challenges can be addressed by focusing on increasing exports through foreign direct investment and by accelerating exports of existing producers; by providing critical logistics infrastructure, including an airport cargo terminal in Kutaisi; by stimulating domestic demand for quality logistics; and by bundling interests and closing information gaps.

Potential of agro-exports to EU

In 2014, Georgia and the European Union established a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA). Most observers hoped that Georgian exports to the European Union would rapidly increase, especially in agriculture.

However, the actual exports of agro-food products to the EU have remained small and concentrated. The limited success is all the more of concern as Georgia has significant potential. With a climate as diverse as California (add Svaneti glaciers, subtract the Mojave desert), Georgia could supply – and traditionally has supplied – many neighboring countries.

As one Swiss-based agronomist put it: “in the North of Georgia, it is cold; to the East, it is mostly dry; in the South, it’s hot; and to the West, labor is more expensive. This puts Georgia’s agriculture in a great spot, longer term.” Similarly, a recent German Economic Team study listed more than a dozen products that should do well in the EU market, including fresh berries, fresh peaches, greens/herbs, and nuts.

Why, then, has there only been a lackluster expansion of exports? Limited volumes, as well as specific barriers in transport and logistics, constrain the growth of agro-exports to the EU.

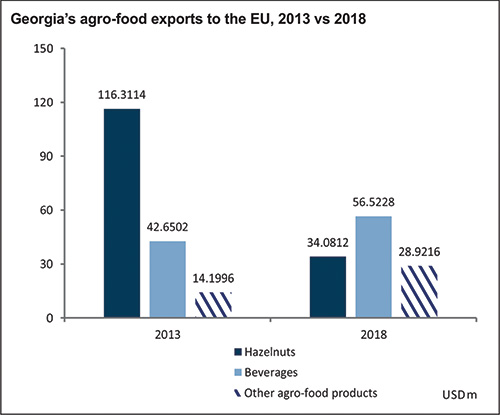

Georgia’s agro-food exports to the EU, 2013 vs 2018

Georgia exported USD 120 million of agro-food products in 2018 to the EU. Exports have, in fact, reduced since 2013. The reduction has been due to the invasion of the so-called brown marmorated stinkbug (see ‘Pushing back the pest – is Georgia beating the stink bug? in the Dec-Jan 2019 issue of Investor.ge), which took a big bite out of the hazelnut harvests, which had been Georgia’s biggest agricultural export category in recent years. Somewhat compensating for this loss, non-hazelnut agricultural exports grew, but from a low base. As UN Comtrade data shows, the exports of beverages grew by 33% from 2013. Other agricultural products increased by 104% but still only stand at USD 29 million for 2018. Exports now encompass a broader range of products, including nut mixtures and jams.

Whichever way you spin the data, the actual export volumes remain low. Limited volumes lead to higher per unit cost for shipping. Additionally, there is no regular provision of transport. As one exporter put it, there is “no established pipeline to Europe”. Consequently, essential logistics services (including advanced laboratories for doing reliable residue tests) often are not yet commercially viable. Georgian entrepreneurs can find it a struggle to get their products to EU clients.

Main export routes to the EU

Currently, trucks typically take one of three routes to the EU. The majority (70%, by one estimate) takes the long road winding through Turkey. The least expensive option is the ferry from Poti to Odessa, though transits through Ukraine are not without complications. A few years ago, entire containers could go astray on that route. The safest and fastest route, according to one European logistics company, is the ferry from Georgia to Bulgaria. This ro-ro (roll-on, roll-off) ferry, however, does not have a regular schedule.

The cost for a refrigerated truck to Western Europe will typically be above EUR 4,000, with seasonal peaks of up to EUR 5,500. For some fruits and vegetables, the advantageous production cost in Georgia can be offset by high transport costs to the EU.

Transporting goods to the EU by ship is cheaper, at around EUR 2,000, but takes longer. Containers require reloading in Turkey or Greece, take 28 days to Antwerp and a few extra days to Bremen, Hamburg or beyond. Trucks, by contrast, take about seven days. A second driver, at extra cost, can cut two days from the trip. For special products, cruising to their markets can be an attractive option. Otherwise, patience is not necessarily rewarded: products that can sail from Georgia could also travel e.g. from Chile, leading to fiercer price competition.

Exporting products by air is viable for a handful of products that are valuable relative to their weight, such as berries or herbs. While flight costs vary, they typically are around EUR 1-2 per kilogram. At this point in time, few airlines offer air freight, nor is there always a full cooling chain if blueberries have to catch a connecting flight.

An added challenge is that most exportable products require special packaging. As export volumes from Georgia are low, such packaging cannot be sourced domestically. Importing packing materials requires time, added cost and prepayment. One exporter says that they import heat-treated pallets. This pallet sells for EUR 17 in Italy yet costs EUR 35 by the time it arrives in the Caucasus. Used pallets are available locally, but exporters do not want to risk contamination when sending their quality products abroad. Some exporters have lost a part of their harvest to frost, while waiting for their shipment of cardboard boxes from abroad.

Exporting wine, blueberries and herbs

The logistics and transport play out in various ways for different products. Wine producers say that they can get their products to Western Europe on single pallets at approximately EUR 500, adding EUR 0.50 to the cost of each bottle. The main headache is organizational. Bundling pallets can help but has its hazards. Some exporters have had their consignment caught up with others’ quality problems.

For blueberries, being shipped out from Tbilisi airport entails a far drive from their ideal – acidic – soils close to the Black Sea shore. There are also not yet enough cooling facilities in the Guria region. Similarly, the herbs grown in a thriving cluster by Kutaisi could be exported by plane. If exported by truck, they mostly wilt when driven beyond Bulgaria.

Four suggestions to increase agro-exports

Our measures could improve export prospects. First, paradoxical as it may sound, volume should be increased for its own sake: more chicken means more eggs. In practical terms, targeted foreign investment would accelerate export growth. The best strategy may be to identify mid-sized investors with access to EU retail shelves to assist in building that export pipeline. For this purpose, a smooth implementation for investment exceptions for foreign investors buying agricultural land remains vital. Volumes can also be increased by accelerating the export of existing producers. Continued access to inexpensive capital, as well as facilities for absorbing growth risks, would help current exporters expand faster. The use of the system of Pan-Euro-Mediterranean cumulation of origin can help to increase volumes also. Georgian producers can still keep the preferential access to the EU market if they use inputs from its FTA partners within the Pan-Euro-Med zone. For more detail, refer to the German Economic Team’s Policy Briefing from February 2020 at bit.ly/Geo-PEM2020.

Providing logistics infrastructure is a key step. Current exporters would like to see more regular ferry service to Bulgaria (or Romania). Most exporters would also welcome a cargo terminal at Kutaisi airport. They believe this would accelerate exports to the EU, though there are several challenges. For example, budget airlines and destinations often do not have cargo facilities. People in the transport sector say they may invest more if there were dedicated logistics zones, in Kutaisi and other locations, close to major roads, with all utilities and building permits.

Stimulating domestic demand for logistics by implementing standards for the local market would increase readiness for export. In that light, the wider adoption of the GeoGAP standard (see GeoGAP – moving towards traceable, safer, sustainable produce in Georgia, in the Feb-Mar 2020 issue of Investor.ge) could develop the logistics value chain, including laboratories. The key in all of this is not just the geographic destination of the EU, but rather the quality of the product. Once Georgian products have EU-level quality, they also fetch premium prices in Russia and even China.

Lastly, business associations (including AmCham, and its Agribusiness committee), donors and the government could bundle interest and close information gaps. There is, as of yet, no comprehensive map of key services, including refrigeration and storage facilities. A business-to-business platform might smooth export transactions. Business associations could focus even more on addressing information gaps and facilitating exchange. Donors can help, but sustainability beyond their assistance will be essential.

The German Economic Team’s full policy briefing is available at .

Interested in joining AmCham’s agribusiness committee? Get in touch with AmCham Executive Director George Welton.

Hans Gutbrod is active in agriculture, teaches at Ilia State University and consults with the German Economic Team.

____________________________ ADVERTISEMENT ____________________________