A Georgian cuppa – reviving a faded world giant in the tea industry

A poor relation to Georgia’s star beverage, wine, it may be, but tea is holding its own both at home and abroad.

Top Georgian tea producer GeoPlant’s Gurieli brand sits on Tbilisi supermarket shelves alongside brands from international giant Lipton, and varietal teas from tiny plantations tucked away in Guria hills are for sale on websites from the Czech Republic and Poland to the UK and US. Not only are tea tastings marketed as visitor attractions across Georgia, but tea tourism, festivals and visits to plantations are on offer along Georgia’s tea-route on global travel websites such as Expedia.

Though not holding strong hopes for a revival of all the thousands of jobs that the tea industry used to supply, the government has been driving a tea plantation renaissance across the four regions with tea history – Adjara, Guria, Imereti and Samegrelo. Lack of high profit margins, and the small Georgian market has limited the industry’s return to the glory of Soviet times – GeoPlant has no major local competitors – but it is making steady progress.

Undoubtedly, there will be a set-back post Covid-10 with tourist numbers plummeting as tea and plantation visits both hold attractions to visitors, particularly those from Arab countries and others, such as Azerbaijan, with strong tea-drinking traditions.

Tea’s history in Georgia is certainly much shorter than that of the vine, but it is a romantic one – a point not lost on its western marketeers and its aristocratic background intrigues many Georgian households. As UK-based tea retailer “Its Tea” tells its website readers (it particularly recommends Georgian Orange Pekoe):

“… tea from the camellia sinensis plant was first brought there by royalty. Georgian Prince Mikha Eristavi travelled to China in the 1830’s, this is where he first tasted tea and enjoyed it so much that he decided he wanted to bring it back home with him. At the time, taking tea seeds outside of China was not allowed so the prince hid the seeds in a length of bamboo and bought them back to his home country and established a tea garden in 1847.

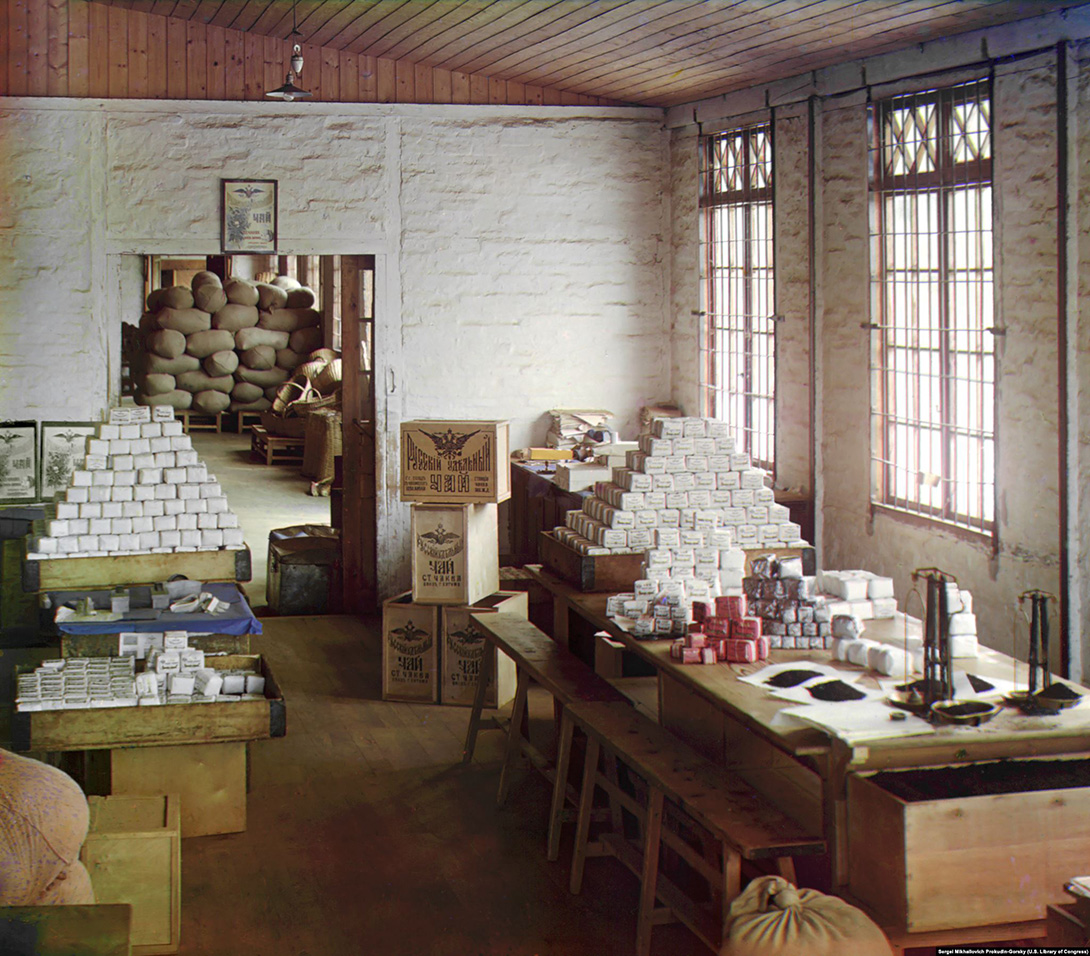

“The climate in Georgia worked well with the Chinese plants, and a new love for the drink emerged over the coming decades. Konstantin Popov, an experienced Russian tea merchant who owned several Chinese tea factories took the Georgian tea industry a step further when he set up a large plantation in the village of village of Chakvi (in Kobuleti municipality) in 1892. With help from Chinese tea masters to cultivate his tea, this formed the basis of what was, for a while, a thriving tea business. The tea even won a gold medal at the Paris World Expo in 1899!”

Popov invited a Chinese tea expert from Guangdong, who came with 1,000 seeds and saplings. Georgia’s warm climate in the valleys of Adjara and Guria turned out to be fantastic for tea cultiva-tion, and sourcing from them avoided the costly transportation across Siberia of Chinese tea. By the 1920s, the Georgian tea business was booming and it became the world’s fourth largest tea exporter.

However, the plantations were collectivized when Georgia became part of the former Soviet Union, and mass production ended the era of quality. With the crop plucked not by hand, but hacked off by machinery propelled by some of the world’s largest tractors, Georgia was relied on to supply just about all the USSRs tea and by the 1950’s remained the world’s fourth most prominent tea exporter. Tea covered 160,000 hectares.

As the online magazine Tea Journey says, the Soviet Union boosted the Georgia tea brand “enor-mously”. Writer Michael Denner points out that “In 1921, Georgia produced 550 (presumably met-ric) tons of tea leaf. By 1966, it produced 226,000 tons. The Black Sea region of Georgia became the “tea pantry” for a vast empire that stretched from Berlin to the Pacific Ocean………Guria had become an industrial powerhouse of tea production.”

Soviet bureaucrats “dreamed of covering the otherwise ’empty’ mountainsides” of Georgia with tea: “Not a single inch of these lands will remain bare,” predicted one early “tea influencer.” Moscow bureaucrats demanded unachievable goals,” Denner adds. From 1917 to 1980, the amount of land devoted to tea bushes increased about 100 times.

Under this harsh industrialization, by the end of the USSR, Georgian tea had lost its cache and flavor. With its markets gone the Georgian tea industry collapsed, the plantations turned into wildernesses and the machinery was sold off to Turkey. Georgians themselves, outside of the growing region of western Georgia and the Azerbaijani-inhabited areas, have never been big tea drinkers, preferring coffee or wine. Their tea purchases are often of exotic looking foreign brands.

A first attempt at a revival came in the mid-90s when Bavarian herbal tea group Martin Bauer decided that Georgia would make a good springboard into the vast Russian market. It started to restore plantations in Zugdidi and Imereti and to diversify into growing medical herbs such as St. Johns Wort. However, this all petered out, and the lead role in tea production was taken up by GeoPlant.

Helped by funding from many of the international financial institutions, GeoPlant is a one-stop-shop for the entire tea production process. It has three major production centers, in Ozurgeti, Zugdidi and Kulishkarli, three primary factories and around six hectares of land.

Founded in 1996, it has strong links in all tea-growing nations and has developed and expanded with the help of their scientific and technical expertise. It has also worked with Georgia’s Tea and Subtropical Cultures Research Institute on production innovation and improving tea quality. Among its trading partners are listed America’s Lipton, Germany’s Plantextrakt and Martin Bauer, Ukraine’s Dobrinia Dar, and others in Turkey, Europe and the Middle East. The brands sell across all continents and Georgian tea also sells into foreign markets for blending as it is cheaper to access than blending teas of the same type from China.

On the marketing front GeoPlant started ten years ago with two Georgian branded teas: “Gurieli Export” and “Rcheuli”, for domestic consumption and export. It added the “Gurieli Fruit Tea” line and “Georgian Baikhi #36”, both of which were also designed for the export market, followed by the “Ali Sultan” brand for the Azeri-settled Marneuli region. Later came “Gurieli Herbal Tea” and the premium “Prince Gurieli” lines. A strong selling point now is the fact that all the teas are organic, “grown without chemicals or pesticides”.

As GeoPlant CEO Mikheil Chkuaseli said at a press conference, following global trends, black tea in teabags was the most popular product. He added: “However, interest towards herbal and fruit infusions is quite high, which is a positive change and hopefully sales in this direction will increase as well,” he added.

In the hills of western Georgia today swathes of old tea plantations have been overtaken by wild plants, fruit and nut trees. But the tea bushes are hardy enough to have survived. The government is trying to lure into the industry overseas companies and small local entrepreneurs and co-operatives. Tea plantations totaling 1,024 hectares had been rehabilitated by the end 2019 at a cost of GEL 2.5 million under the state’s 2019 Rehabilitation Program of Georgian Tea Plantation, approved with the aim of putting 7,000 hectares back into production. Unfortunately for the new producers, according to an ISET study for the EU albeit a couple of years ago, farmers were receiving only 4 percent margins and processors 12 percent while brokers received 59 per cent and retailers 24 per cent.

However, the way of life is attractive. Miina Saak is one of a group of friends from Estonia and Lithuania who left corporate jobs at home and moved to Georgia “to work with our hands again.” Saak and her friends founded Renegade Tea Estate at Tkibuli to take advantage of the Georgian government’s assistance in setting up on a rented plantation. Europe has been their target market.

One of the successful Georgian SMEs is ‘Green Gold’, produced in Laitrui in Ozurgeti by Tamuna Khabeishvili. This is an organic tea grown on 25 hectares in the village of Nagomari, and can be found on the shelves of Goodwill, Europroduct, and in the restaurants Keto and Kote, Barbarestan, and Shushabadshi.

Rather than farm, Kona is looking to better margins, producing and blending. As Natalia Partskhaladze told scmp.com food and drink online magazine: “We collect artisan loose-leaf teas directly from small farmers. In our bouquets, we only use Georgian tea from Guria, herbs that we grow in our greenhouse and we collect in the wild from all over Georgia, along with the spices and flowers we import from all over the world,” she says. Kona, which was supported by EU agricultural development programme Enpard, has nine gourmet teas, and artisan black, green and bilberry. One with foreign investors is Gurian tea “Gamarjoba”. It plans to appear on the market this year and, backed by Czech partners, is already on Czech markets.

Export markets like the flavor of Georgian tea, as the slow growth on the hills of western Georgia gives “the tips of Georgia’s tea bushes a uniquely sweet, mellow flavor perfect for high-end tea”, according to Radio Free Liberty. Georgian tea has many foreign fans, such as tea expert John Snell. Describing the opportunity for Georgian tea, he writes on the UN Food & Agriculture Organisation website that “new tea plantations have been established …. and some incredible leaf teas have been produced, taking us back to the age of Lao Jin Jao, whose Georgian tea won the gold medal at the Paris Expo in 1900.”

____________________________ ADVERTISEMENT ____________________________