Georgian waters flowing towards new export markets

Water is now very much on Georgia’s mind after a year of weather extremes, with little snowfall in winter and poor rainfall in the spring. However, new export markets in the Middle East are thirsty for Georgian water and green-bond funded infrastructure projects aim to help better manage the country’s waterway resources.

With its 26,000 rivers, over 2,000 mineral water springs, 800 lakes, 734 glaciers, and two huge snow-covered mountain ranges, water is something that until recently Georgia has largely taken for granted. But in a world of rapid climate change, water-related issues are rapidly coming to the fore, presenting both new opportunities and new challenges.

At one extreme, exports of mineral water are climbing, with drought-hit countries in the Middle East slowly emerging as new markets in addition to the traditional former FSU buyers of Georgian brands, and they and Georgia’s water utility businesses are attracting millions of dollars of investment.

At the other, the Caucasus glaciers are melting, causing floods, landslides and erosion and exacerbating the devastation from rain, which now seems to come in torrents of monsoon dimensions – a trend forecast to worsen, as witnessed this summer in Racha.

However, when it comes to Georgia’s mineral waters the story seems to be undiluted good news.

Fresh names are appearing on supermarket shelves and there is plenty of potential for more as Georgia has no less than 730 kinds of mineral waters suitable for balneological purposes and industrial bottling – even more than its grape varieties.

Just a tiny number of these are used either commercially or recreationally – eleven are listed in the National Standard of Georgia “Bottled Natural Mineral Waters”. Only five of these are fully exploiting their potential – Borjomi, Nabeghlavi, Sairme, Mitarbi and Phlate, according to a journal on Georgian mineral water by nine specialists at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University’s Alexander Janelidze Institute of Geology, who are promoting the possibilities for Uraveli, a mineral water deposit near Akhaltsikhe.

Assessing the Georgian mineral water market, research group Euromonitor states that “while Borjomi no longer leads brand sales in bottled water, strong awareness and trust in its quality have supported the expansion of other brands, making the company’s product portfolio the widest on offer. Although Borjomi Georgia leads overall bottled water sales, the most popular brand in current value terms in the category is Nabeghlavi carbonated bottled water by Healthy Water. Initially positioned as a cheaper brand, Nabeglavi managed to gain popularity within a category where competition remains quite limited.”

The Georgian tour company – Geofit Travel – is marketing most of the country’s main mineral springs and spas as destinations and finding others barely heard of. Of course, it starts with Borjomi then continues with Nabeglavi, whose water comes from the Gubaseuli River Gorge in Guria’s Chokhatauri District; there is Sairme, sited 55 kilometers from Kutaisi in Baghdati district; the Gurian resort of Bakuriani deposits are producing low-mineralized water; Lugela mineral waters are located in the Chkhorotsku region near the village of Mukhuri in the Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti resort of the same name; Zvare’s deposit, which is rich in iodine, is located in Imereti; Tskhaltubo, seven kilometers from Kutaisi is famous for its thermal radon mineral waters; Shovi, from the mineral springs of the village of Shovi in Racha, has water of several types; Likani is in the Borjomi valley at an altitude of 810 meters above sea level; Mitarbi comes from near the village of Patara Mitarbi in the Borjomi region; Bakhmaro is sourced from the mountainous resort in the Chokhatauri district of Guria, and lastly there is Sno, from southern slopes of the central part of the Greater Caucasus.

Newer on the market is Gudauri mineral water, which, according to its press releases, started exporting last November, targeting the Russian market. However, its ambitions are for the Arab countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates.

Mineral water exports last year, according to Geostat, totalled $132.6 million and bottled fresh water neared $1 million, together achieving a rise of 17.6 per cent. This went mainly to Russia ($60 million), then Ukraine ($23 million), Lithuania ($15 million), and Kazakhstan ($14 million). Following were Belarus, Uzbekistan, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, China, Japan, Armenia, and Turkey.

Western markets included Japan, Israel, Greece, Germany, the US, and Canada. Figures for 2020’s first quarter reflect the impact of COVID-19 on this business, with sales down 11 percent at $30 million.

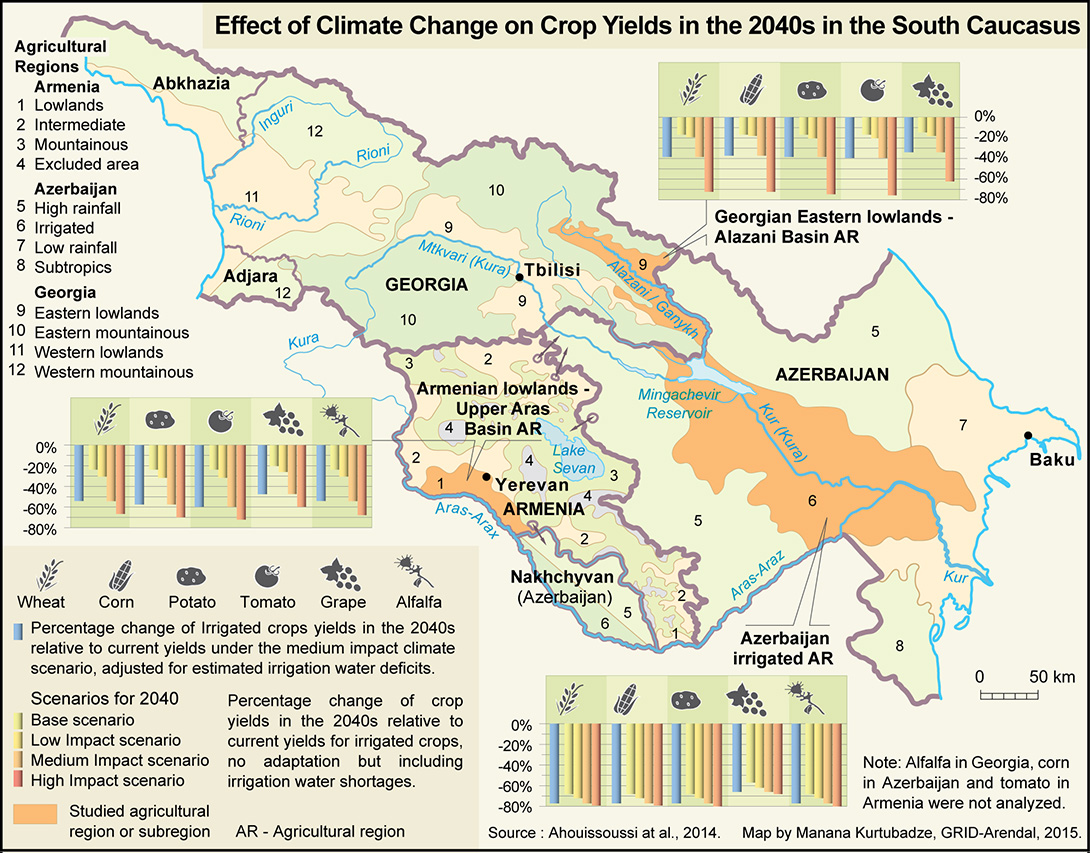

Water-based trouble with their neighbours is another dimension raised in various regional reports on water and security, pressing for agreements on sustainable management for transborder river systems as competition for water increases. Such agreements have yet to be reached in the South Caucasus.

As Conflict and Cooperation in the South Caucasus: the Kura-Araks Basin of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, a report discussing the views of the OSCE, USAID/DAI, TACIS and NATO, pointed out: “In general terms, Georgia has an oversupply of water,

Armenia has some shortages based on poor management, and Azerbaijan has a lack of water. The main use of Kura-Araks water in Georgia is agriculture, and in Armenia, it is agriculture and industry. In Azerbaijan, Kura-Araks water is the primary source of fresh water and is used for drinking water. Almost 80% of the countries’ wastewater loads are discharged into the surface waters of the Kura-Araks Basin.”

In Azerbaijan, Eurasianet reported over the summer, the state of water supplies in Azerbaijan was reflected in the fact that residents of Baku’s Ramana district have “for several years only had water for two or three hours a night.” They add that the country’s state television reported in June that the Kura’s level had dropped 2.5 meters in some places in recent months, causing water from the Caspian Sea to flow back into the river rather than – as usual – the other way around. The level of the Mingachevir reservoir, which is fed by the Kura, had dropped by 16 meters.” The government said in July that it is examining the water situation ‘urgently’.

Water’s potential as a source of regional conflict, as well as of environmental damage, has not been lost on the EU, which has been pushing for the introduction of monitoring and co-management.

The European Union Water Initiative Plus for Eastern Partnership (EaP) Countries, which is the biggest commitment of the EU to the water sector in the EaP countries, has been helping Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine to harmonise river management and bring their water legislation closer to EU policies. It also addresses the challenges of developing efficient operational controls and cost efficiency.

While overall Georgia has plenty of water, poor access and sanitation is still a problem, especially in rural areas, according to a WGO/UNICEF paper which cites 2018’s Geostat figures that 51 per cent of Georgians had no direct access to modern toilet facilities.

While progress is being made, it added, some of the infrastructure was outdated or had been destroyed, while in other places it has never existed. The government has made improving the situation a national priority, but online magazine Caucasus Voices commented that the problem was complex and extremely costly and time-consuming to solve. Indeed, work has been going on for years with the help of the EU and international organisations, and in 2019 alone the government put 300 million GEL towards repairing water supply and sewerage systems.

Investment has continued this year. The United Water Supply Company announced 202 million GEL to be spent on 67 water and sewerage infrastructure projects throughout Georgia in 2020. Also, as part of the on-going EU programme the French Development Agency agreed to provide €58 million in July for a project to finance the reconstruction of water and sanitation utilities in Khashuri.

In the same month, in a first for Georgia, “green bonds” to finance the upgrading of Georgia’s water and sanitation were announced by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for modernizing Georgia Global Utilities (GGU) infrastructure. GGU is owned by London stock-market-quoted Georgian Capital (which was formed by The Bank of Georgia).

The ADB itself is putting up $20 million and a further $20 million will come from Asia’s Leading Private Infrastructure Fund and be administered by the ADB. The director of the ADB’s Private Sector Operations Department, Shantanu Chakraborty, said: “ADB’s assistance will help ensure that communities in and around Tbilisi are supplied with water 24 hours per day, and that water supply and sanitation systems in those urban centers function properly.”

Funding is also being sought to repair and restore Georgia’s balneological infrastructure, as mineral waters are such an important feature of the country’s tourism.

While Likani and Borjomi have been given restoration treatment, the former luxurious Soviet spa town of Tskaltubo is now a museum of decaying splendor, most of its elegant sanatoriums abandoned, roofs open to the sky, and home only to refugees.

Invest in Georgia’s dream has been that Tskhaltubo, so famous between the 1930s – 1950s, should once again be a prestigious international water playground, and “the 2nd largest Medical and Wellness SPA destination in Europe”.

Because of Georgia’s complex geography, there are also predictions for some parts of the country to experience more droughts. In Shida and Kvemo Kartli, Kakheti and Upper Imereti, the frequency of droughts has already increased, “almost threefold in recent years” says a report on the outlook of climate change adaptation in the South Caucasus mountains, published last year with the support of the United Nations Environment Programme.

A Swiss funded paper from Focal Point Climate Change and Environment Network, also recently published, states that “the Caucasus will likely no longer rely on sufficient rainfall to meet summer demand by late century with increased dependence on depleted snow and glacier meltwater resources.”

Georgia’s average temperature rose 1.3°C, and the level of precipitation by 60 mm between 1990-2015, and is expected to increase by 3.5 °C by the end of the century, forecasters suggest.

On rainfall, the paper says: “precipitation is expected to increase in nearly all the territory up to 2050, but then drastically decline towards 2100”, adding that “increases in heavy precipitation are expected with a concomitant risk of increasing floods, flash floods, mudflows and landslides in the mountain areas.”

____________________________ ADVERTISEMENT ____________________________