Batumi bottleneck puts Adjara on the map as birding destination

What started as an idea for a small ornithology project has generated, three decades later, a fast-growing eco-tourism business for Adjara and one of the world’s most important birding locations.

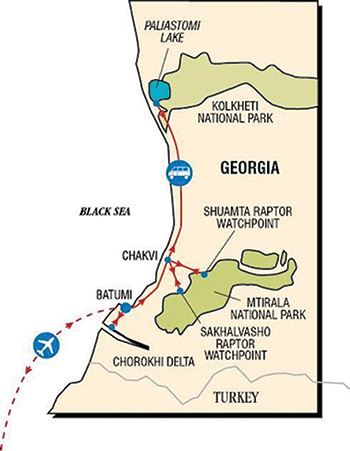

This is the monitoring of a million and a half raptors – 34 species of eagles, ospreys, vultures, buzzards, kites, sparrowhawks, falcons and harriers – and hundreds of thousands of other birds that has become a bi-annual event at the “Batumi Bottleneck”. Their migration routes bring them through this Georgian crossroads as they navigate between African winter feeding grounds and Eurasian spring breeding areas, which has opened up a whole new branch of tourism for this part of Adjara.

The Batumi Raptor Count (BRC) began as merely a monitoring organisation when it was established in 2008, but, it says “after realising the scale of the hunting pressures that migratory birds face in the region, BRC’s mission has now expanded to that of a conservation and monitoring NGO.” As part of this work it has been promoting local guesthouses where visitors can watch the spectacle of more than 50,000 raptors migrating in a day while directly contributing to the local economy. “This has helped us gain support among the villagers to reduce the illegal hunting of birds.”

Right now, the BRC is calling for volunteer coordinators and counters to spend at least 14 days on the watch sites at the villages of Sakhalvasho and Shuamta, north of Batumi, during the two-and-a-half month autumn migration season. This year it runs from August 12 through to October 21. “Novice as well as experienced counters are welcome”, it says (more information on this opportunity can be found at https://www.batumiraptorcount.org/volunteer). The BRC is also, of course, seeking funding, and a target of EUR 20,000 has been set for 2022 – which is well on the way to being met.

Since internationally there are tens of millions of “birders” (the popular term for bird-watchers), mostly among the well-off middle classes, the BRC is proving to be a money-spinner. At the same time, by creating local HoReCa business, helping develop home-stays, guesthouses, and small hotels, it has made a substantial impact on the local communities and is providing an incentive that helps to protect the birds from widespread illegal shooting.

Education efforts seek to engage locals in conservation efforts

The need is dire, as illustrated by the following encounter at a recent count between an ornithologist and a young local falconer: “We were near one of the watch sites chatting about the weather when he broke off to cock his gun and sent a volley casually into a flock of low-flying honey-buzzards. He then turned to pick up our conversation again,” the aghast ornithologist told the online journal BritishBirds.co.uk. Until 2008, it was not only the number of migrating birds that was unknown, but also the size of the illegal carnage. The Georgian carnage numbers are still uncertain but most likely run in the tens of thousands, and Georgia is just one section of the migration route.

Raptors are threatened with extinction in many parts of the world. For example, in North Africa, according to the Swiss-based International Union for Conservation of Nature, half of the raptors breeding there are threatened. A combined report from researchers at several U.S. universities, The State of the World’s Raptors: Distributions, threats, conservation and recommendations states that “…18% of raptors are threatened with extinction and 52% have declining global populations.” This, it warns “is concerning, not just because ….the reduced abundance of raptors can have cascading effects on ecosystems…sometimes acutely impacting human well-being because of their scavenging behaviour” as well as allowing rodent populations to thrive.

Historically, migrating birds have been hunted to capture live birds for Georgia’s thriving age-old tradition of falconry. Falconers trap juvenile Eurasian sparrowhawks and goshawks to train. Some are killed for food, or most often, surveys found, are shot just for pleasure, according to the report “Mapping the conflict of raptor conservation and recreational shooting” by academics at Hungary’s European University.

The BRC has ambitions to increase its local conservation impact not only by promoting western Georgia’s avi-tourism but also working with local schools and universities. Its team has been “putting Batumi on the map as a top birding destination during spring as well as autumn; to expand our reach to other communities in the region by developing educational materials and supporting teachers in establishing ‘bird clubs’; and to build an alliance with traditional Georgian falconers as stewards for raptor conservation….. The more people that visit Georgia because of the raptor migration, the more alliances we can build with Georgian stakeholders.”

Money from WWF Holland is financing a training program to help relationship-building with young falconers, and funding from British Birds Charitable Trust and BirdLife Netherlands is training teachers in environmental programs and conservation. With all these efforts, says BRC, “attitudes towards raptors have changed in our host communities.” There was already a basis on which to work in that “hunters have a positive attitude towards hunting ethics – such as no shooting in spring and the concept of quotas.”

Black Sea flyway on the radar for birders

Twice a year, billions of birds migrate vast distances across the globe. According to BirdLife International, an international partnership of conservation NGOs, typically, these journeys follow a predominantly north-south axis, linking breeding grounds in arctic and temperate regions with non-breeding sites in temperate and tropical areas. Many species migrate within migration systems along broadly similar, well-established routes known as flyways. Recent research has identified eight such pathways: the East Atlantic, the Mediterranean/Black Sea, the East Asia/East Africa, the Central Asia, the East Asia/Australasia, and three flyways in the Americas and the Neotropics.

Batumi is in the east African-Palearctic migration system and on the Black Sea flyway, with many other smaller local flyways feeding into it. Africa is “one of most important wintering regions, the birds’ destination being tropical non-breeding areas during the rainy season from August to October. There, at constantly high temperatures, rainfall promotes the development of vegetation and, consequently, determines the abundance of herbivorous invertebrates”, according to The Royal Society, the world’s oldest scientific academy.

In preparation for the flight from Georgia, substantial numbers of raptors converge in large valleys and along watershed areas in both the Greater and Lesser Caucasus range, for example at Kazbegi, the Mtkvari valley, Alazani, and the Javakheti Plateau. “The Black Sea, in combination with the lush subtropical foothills, which in the hot and humid fall produces warm updrafts or thermals, present an energetically ideal gateway for passive migrants like soaring birds-of-prey (for example thousands of Honey-buzzard Pernis apivorus), but also to countless more active flyers like Accipiters, harriers and falcons and other birds….”, comments a report by Econatura in Raptor Migration and Bird Conservation Challenges along the Eastern Black Sea Coast.

According to a report in BritishBirds, Batumi was, for a time, “something of a blind spot for the international birding community.” This is despite the fact that Russian ornithologists noted the massive aggregation of migrant raptors at Batumi way back in the 19th century. More recently, Georgian anthropologist Andrew Abuladze organised counts through Georgia in the 1970s, and a number of reports commented on the volumes of migrating birds along the Black Sea coast. Counts were very limited at the end of the last century and serious efforts to prospect for a raptor count were not launched until 2007.

At that time, two Flemish biology students (Brecht Verhelst and Johannes Jansen, who still run the count) developed the idea after observing thousands of honey buzzards darkening the sky for hours on end as they flew along the bottleneck where the Lesser Caucasus meet the eastern Black Sea coast. There, they hatched a plan to conduct a two-month autumn raptor migration survey with international volunteers, bringing in biology students from Georgia and abroad. It was effectively an international youth exchange and was funded by the EU’s Youth in Action initiative (which would later become Erasmus+). The high level of raptors counted put the Black Sea flyway on the radar of bird migration enthusiasts worldwide. Last autumn, 1.4 million raptors were counted, with honey buzzards accounting for a third.

While raptors are the main focus of the count, many other species of birds are observed from the station – hundreds of black and white storks, cranes, turtle doves, pelicans, pigeons, owls, swifts, strikes, buntings, bee-eaters, orioles, nightjars and European rollers fly through – sometimes daily – negotiating the thermals and autumn’s dense cloud cover.

Another attraction of the count, especially early in the season, is “the sheer numbers of birds combined with the ‘organised’ nature of the bulk of the migration. It makes for an excellent introduction to raptor identification and migration dynamics,” says BritishBirds.

Publication of the data with open access says a paper on the count from University of Amsterdam, should “reinforce the global importance of the eastern Black Sea flyway for migrant birds.” Considerable work has been put into systems to avoid double counting, automating the count, and validating the data after intensive searching for errors.

Encouragement that such projects can work can be found from the conclusion drawn in the U.S. report “The State of the World’s Raptors: Distributions, threats, conservation and recommendations” as it points out that “conservation efforts have saved several raptor species from the brink of extinction”. Education is the most powerful driver for conservation, and there are a number of organisations funding it, including the U.S.-based Peregrine Fund, which runs a Global Raptor Impact Network.

Tourist revenues are, however, the raptors’ best hope, persuading local populations to protect the birds. Hence, one of the important activities of the BRC is promoting it. They have even initiated a Batumi Birdwatching Festival, which this year takes place from September 2 to 8. Fortunately, birder numbers seem to be rising.

In the U.S. alone, bird-based tourism attracted 47 million people a few years ago, and interest is increasing, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), with 38% of that number taking trips away from home. Interest was greatest, it said, “among higher income groups” and college graduates – more so for women than men (56% as opposed to 44% were birders). The FWS gave a somewhat staggering figure for trip and equipment-related income, which generated $41 billion and recorded total industry output of $107 billion. Another U.S. study from the USDA Forestry Service found similar birder numbers. In Europe, the UK registers the largest number of birders, with spending put at around $500 million a year by Acorn Consulting Partnership. Moreover, 37% of all European tour operators offer birdwatching tourism.

A measure of success for BRC is that Batumi birdwatching is now well established on the tourism map – a Google search for bird-watching holidays in Georgia brings hundreds of results!

____________________________ ADVERTISEMENT ____________________________