How to build an ‘Old Town’: Tbilisi’s architectural past and where it stands today

In modern Tbilisi, debate and discussion around architecture is fierce—and understandably so. Tbilisi has long been a hodge-podge of architectural styles, ranging from the towering buildings constructed under the Russian Empire to the amorphous glass-and-steel buildings that came to define Saakashvili’s time in power.

Representing much of Tbilisi and Georgia’s history, the old town holds a firm place in the heart of these discussions. But this story is not one easily told. When exploring this complicated history, it quickly becomes apparent that the tale of dzveli Tbilisi (Tbilisi’s Old Town) represents both the good and the bad of the city’s architectural practice.

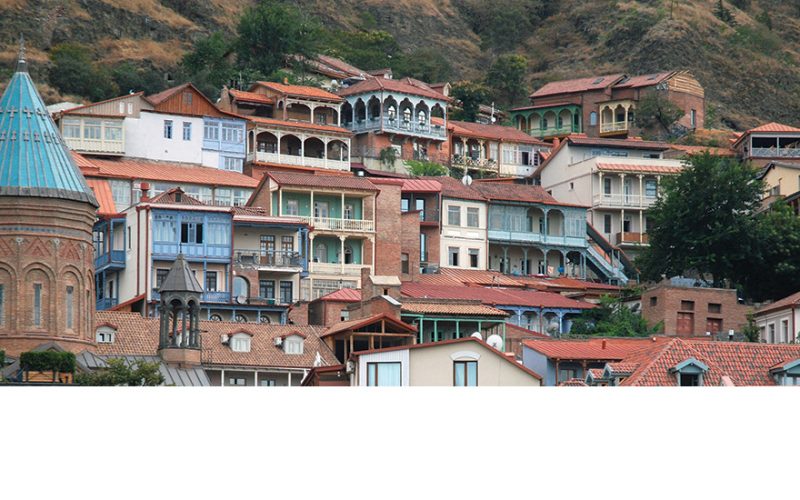

First, a modern introduction. Basking in the shadow of the 4th century Narikala fortress, the old town offers a culturally-tangled cobweb of stunning streets and alleys, perfect for locals and tourists alike to lose themselves on a crisp autumn day. Arriving at the bottom of the hill, a visitor can relax in one of many sulfur baths of Abanotubani, washing away the troubles of the day with a refreshing, if a bit aggressive, scrub.

According to legend, Abanotubani was the area that birthed Tbilisi. The legend states that in the fifth century, Iberian King Vakhtang Gorgasali was hunting in the forests of the original Georgian capital, Mtskheta, when he managed to kill a bird. He then sent his falcon to find his kill, only to lose sight of both birds soon after. He set off, eventually landing upon the hot springs that would someday give Abanotubani its name.

“It is exactly in this place that King Vakhtang found his falcon boiled in a hot spring. He put his hand into the water and discovered it was warm, and he said: ‘I will found a city here and we will name it Tbilisi, which means the warm city,” Vlasi Vatsadze, a local tour guide, explained to Euro News.

By fate or fluke, Tbilisi positioned itself in an area that would make it a central trade stop for burgeoning international markets. Unfortunately, this also meant war. From the late 6th century to the early 19th century, Tbilisi was repeatedly sacked. Each time, parts of the city were destroyed, their buildings occasionally reconstructed in styles that bore passing resemblance to the features that came before, but frequently making massive changes. By the time the Russian Empire took over in 1801, Tbilisi was an architectural funhouse: Persian houses seated next to Armenian constructions, refurbished Roman-style halls bookended by Byzantine houses.

As the Russian Empire took control, they sought to change the diverse architecture of the city. While a portion of buildings were destroyed, the Empire mainly focused on expansion, unifying the city under a central architectural design plan and street layout based on other major European cities.

When the Soviets arrived, they brought both an imagined excess and a dark practicality to their constructions. On main streets, broad facades from the period under the Russian Empire were joined by impressive Stalinist buildings that gave a feeling of invincibility and strength to the city. Behind the scenes, concrete slab buildings were erected, providing the ever-growing population with pragmatic, though emotionally hollow, housing solutions.

All the while, the old town simply continued to be the old town, and little care was given to its maintenance—that is, until tourism came into play. Near the end of the USSR, a tourist industry had blossomed across Soviet states, and soon, people were traveling to see Tbilisi not only for the city that it is, but the city that it was—or whatever was left of it.

This left Soviet Georgia in an odd predicament. Yes, the old town needed to be reconstructed, but how does one ‘reconstruct’ an area with such a long and storied history? Does one pick an era of existence and try to return it to that style? Or does an architect attempt to capture the mixed-history oddity that made the city so unique in the first place?

A modern take

To resolve these questions, the architect Shota Dmitrievich Kavlashvili was hired. Unfortunately, Kavlashvili was immediately struck with the same dilemma.

“On one hand, the task of preserving the historical part of the city — with narrow streets and a small scale of development — needed to be facilitated. On the other hand, there are difficulties: what is considered valuable and what is not? And how to identify this value?” Kavlashvili asked in an interview with Vokrug Sveta in 1983.

Instead of focusing on the past, Kavlashvili opted to recast history, using the lens of Tbilisi’s past to create a new idea of the city through his architecture. Some buildings were demolished. Others were refurbished as best was possible. Even more were reconfigured, doing away with the closed-off staircases and balconies of yore to make way for open-plan constructions designed to facilitate conversation and neighborly interaction.

It was not an accurate depiction of Old Tbilisi’s architectural past, but it was an attempt to represent its historical nature: a place where people met, conversed, and exchanged goods and information.

“We largely based our work not on what Old Tbilisi was, but on our ideas of what it should become,” Kavlashvili explained. “It’s like a dream taken from the past and turned to the future.” For his work, Kavlashvili won the USSR State Prize in the field of literature, art, and architecture in 1987.

But things in the old town would not stay stagnant for long. Under Saakashvili and Tbilisi Mayor Gigi Ugulava, work on a project entitled “New Life for Old Tbilisi” began.

The motivation for this project was twofold. First, it sought to rehouse those living in the unsafe homes that still populated the old town. Second, and more importantly, it was an attempt to revitalize the construction industry that had come to a halt after the 2008 war and global financial collapse.

However, this was a controversial endeavor. To complete the vision of “New Life for Old Tbilisi,” many buildings were demolished, some with known historic value. And while the city had instituted a classification system in years prior to ensure that buildings of historic value would be preserved, these classifications were frequently ignored to make way for new construction. Often, there was little attempt made to preserve aspects of the historic structures that were being renovated or replaced.

“Look at that! They took out the old bricks there and used brick cladding! And they attached a balcony there — what for?” asked Maia Mania, architecture historian and professor at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts, to New York Times journalist Joshua Levine in 2013 while on a tour of the reconstructed Old Town. “I am ill with what they have done in Old Tbilisi.”

Furthermore, while some residents were receiving new housing, the project was slowly being seen in the public as an attempt to raise real estate prices rather than a genuine attempt to restore the area.

“In cases where developers were hired to ‘renovate’ historic buildings instead of just demolishing them, they were pressured to increase the floor space of the original structure as much as possible, so as to get a larger return on their investment upon selling back to City Hall,” wrote author Angela Wheeler in 2012.

Protests erupted. Citizens of Georgia poured into the streets to make their voices heard against the renovation of the Old Town and the destruction of Tbilisi’s buildings across the city. Many took issue with the project’s practice of ‘facadism,’ or the preservation and restoration of only the building’s outer shell while gutting the interior of the building almost in its entirety.

“What does preserving historic facades mean? If a building is a historical monument, then that’s in its entirety – doors, windows, stairways and all,” protestor Tamar Amashukeli said to journalist Teo Bichikashvili in 2012. “This way, we’re getting a new building with a similar façade but without any historical or cultural value.” By 2012, Georgia-based writer Peter Nasmyth estimated that one third of Old Tbilisi had been destroyed.

The story continues

As time passed and renovations of the area continued, a new government administration took over in 2012 and began implementing their own renovation projects. Dubbed “New Tiflis,” this construction and revitalization initiative focused on renovating the historic city, adding new areas for tourists, and creating more recreational areas across Tbilisi. Its initial aims focused on Agmashenebeli Avenue, Gudiashvili Square, the Dry Bridge, Orbeliani Square, and the surrounding areas, with room for expansion as time progressed.

But this project has not been without its own criticism. While government officials made a point of including the area’s history in discussions of its renovation, with Agenda.ge reporting that “more than 200 professionals including architects, historians, urbanists, and art critics” were consulted by the government, many have criticized this project as a real estate move similar to that of “New Life for Old Tbilisi.”

“What was once a green and picturesque street has lost its tree and vine cover to strangely uninviting benches and expensive cafes, a change that can be heard lamented in conversation with families living just off the renovated street,” writes Robert Isaf. “As a result of the influx of foot traffic, and especially touristic foot traffic, many courtyards on the street keep their gates closed that through daytime would have been open before; cars are exiled from their owners’ yards on account of restricted access times; and rising prices encourage tourist-oriented businesses in buying out residential owners, further fracturing long-established communities.”

Isaf is not alone in his critiques. Proposed developments on Mirza Shapi Street, which sits above the Abanotubani sulfur baths, attracted a number of protesters in 2018. At one of the protests, urban policy activist Nata Peradze expressed concern that excavation of the cliffs to build two large multi-functional complexes in the old town area was destroying the harmony of the landscape and architecture, noting that “building does not always stand for development.”

Despite continued controversy around how to best preserve the city’s cultural heritage, renovations of Tbilisi’s old town have continued. In 2018, the new Aghmashenebeli Avenue made its debut, featuring the renovation of 47 historic houses at a price of $13 million. One year later, the newly renovated Orbeliani Square opened. The project reportedly cost $31 million, and 20 buildings were restored in the process. Gudiashvili Square, which was also renovated, opened in 2021, and in 2022, the government announced the renovation of Metekhi Bridge, one of the oldest bridges in Tbilisi, at a cost of just under a million dollars.

These projects are in addition to other works under the New Tiflis umbrella, such as the renewed Dedaena Park and surrounding green space, which was officially finished in 2021 at a cost of around $9.5 million. Future projects for renovation include the streets of Sulkhan-Saba, Ingorokva and Gorgasali, and Phase 2 of the Narikala Fortress rehabilitation is planned within the next two years.

Tbilisi’s architecture tells its long and rich history, and every new generation has left its mark on the city. As more buildings are constructed and others renewed, the story continues.