What’s moo-ving the Georgian milk industry

Georgia is heavily reliant on imported milk powder or frozen milk to produce its dairy products. However, years of efforts to stimulate the industry are slowly allowing the quantity and quality of Georgian milk production to rise

“Say cheese!” – the command used by photographers to elicit a smile is being beamed by the government at Georgian milk farmers which own the country’s half a million or so dairy cows. It wants them to make more cheese, but under the ‘Georgian Milk Mark’ which certifies that the cheese comes from fresh natural milk (and contains no powder or vegetable oil) and has food safety certificates (HACCP – Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points). The aim of this scheme, launched last March, is to replace the informal production that supplies the cheese found in markets and most small shops and to comply with health and sustainability requirements of the Association Agreement between Georgia and the EU.

The Georgian Milk Mark, administered by the Business Institute of Georgia, is becoming one of the rare stories of successful local brand building. There are now nearly 20 dairy enterprises collecting milk from the grass-fed cows of thousands of small producers turning out “ecologically pure” dairy products at clean, regulated premises, all part of the Alliances Caucasus Program (ALCP). This is a 12-year-old, $2.7m Swiss Development Cooperation project which is being carried out in cooperation with the Austrian Development Cooperation and implemented by Mercy Corps Georgia. Colorfully wrapped Georgian Milk Mark products are sold through all the major supermarkets, most small corner shops and to restaurants.

“Informal, non-compliant cheese production is still widespread,” comments a study for ALCP from the United Nation’s International Labour Organization titled “Better cheese, better work”. But this year legislation should change that, making it mandatory for producers owning more than five milking cows to register and become subject to inspection.

That is not the only driver for change. ALCP has been highly innovative in accessing the media both to educate small cheese makers (mostly rural women) and in marketing.

“Lack of information”, ALCP found, was one of the main causes of small farms’ “exclusion from profitable agriculture markets” and operating outside food safety nets, most getting what information they had from neighbors and friends. ALCP believes TV, radio and newspapers were the best education media. Yet, as it notes, “agricultural journalism did not exist in Georgia a decade ago” and none was targeted at the main players, which in the case of dairy is the women on farms.

So, it set out (and has succeeded) to build regular agricultural coverage. For example, nationally on TV there is now Agri News, and Chveni Perma (which became Perma), in Adjara there is Me Var Permeri, in Samtskhe-Javakheti there is Farmers’ Hour, on Marneuli TV there is Tanamedrove Meurne. There are several regular regional newspaper features. There are lessons on the internet and mobile apps, and interactive platform agroface.ge also carries veterinary inputs. All ALCP media products are now independent, it says, and half of surveyed viewers “report changing their agricultural practices” as a result of what they learnt.

There are a lot of reasons for reforming dairy production. Livestock dominates agriculture, which employs around 40 percent of the country’s labor force. “Many rural families livelihoods depend exclusively on the livestock they breed, notably cows,” comments an ISET Policy Institute analysis for USDA Food for Progress, “… milk production still represents a significant proportion of smallholders’ incomes.” Hence the widespread concern about the adverse trends that have been developing in recent years.

For a start, as ISET found in its 2018 survey, Georgians like their dairy products, especially their Georgian cheeses (although at an average of 170 kg per annum per capita they consume less than the EU’s 250kg), for which the majority of Georgian milk is used and the market for which ISET valued at around GEL 1 billion. However, “while the demand for milk and milk products has an increasing curve, Georgia is a net importer of milk and dairy…” Dairy self-sufficiency has been decreasing, as have the number of cows as demand for live animals for export bites.

Georgia does export some dairy products – US$2.8 million-worth in all in 2018, of which US$289,00 were Sulguni, Imeruli, Tenili and Guda cheeses – but almost all goes to neighboring Armenia and Azerbaijan rather the desirable EU markets.

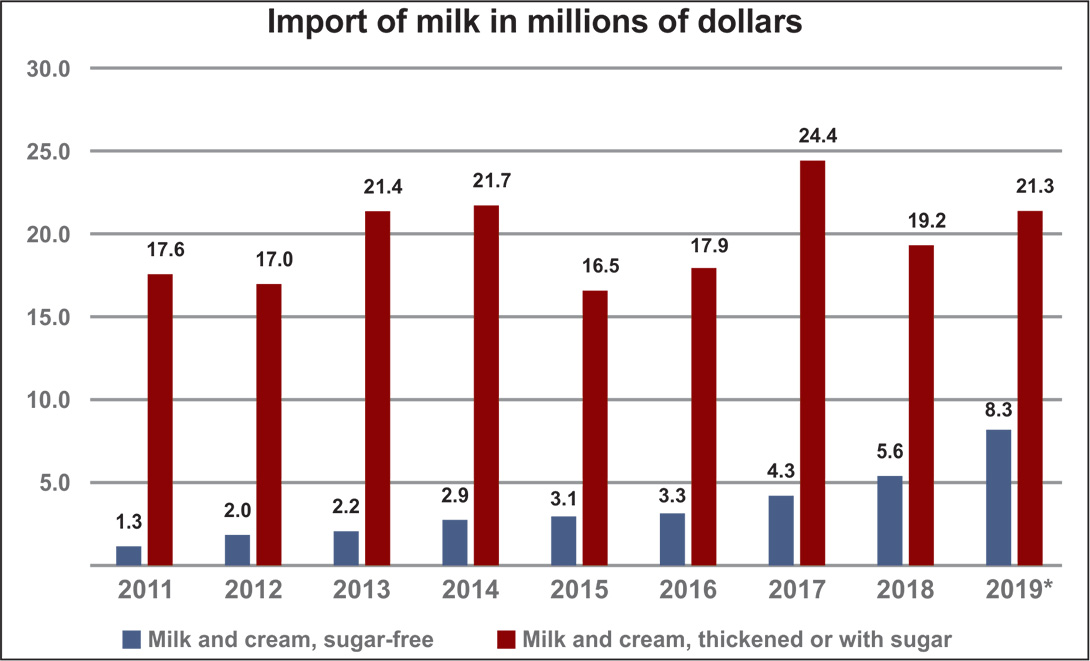

Cow productivity has been falling, and, making life difficult for producers, and milk supply is seasonal. Milk prices have become “at least two times higher in Georgia than in the European Union” the study found. Local milk supply fails to meet demand and the import of milk powder has been rising – in 2018 these were worth $15.8 million, 2.5 times more than in 2009, says ISET. Imports of butter, cheese and curds have also been rising, and were worth $10 million in 2018, major suppliers being the Ukraine and Russia.

Then, there is the question of productivity, with the 15 large industrialized farms far outstripping the 200,000 or so lowland and mountain small holders by as much as six times. “The various types of farms have different challenges, but a lack of knowledge, experience and qualified specialists (e.g. vets) are common problems for the vast majority of farms. The low productivity of cows, typically found in mixed farming, is caused by poor productive breeds, a deficiency in proper food (ie concentrate, silage) and a lack of appropriate treatment for animal health,” ISET states.

That is only a start. The milk processing and collection system is equally fragmented and problematic, most production being done by “unregistered operators”, either in the farmers’ own homes or by small businesses. In 2018 there were only six factories, it adds.

The informality, paucity of knowledge and difficulty accessing good veterinary services, the low productivity and profitability all mean that there is “a lack of surplus income for upgrades, health and hygiene compliance” or capacity increases. ISET gives the example that: “It is estimated that an adoption of better feeding and lactation period management practices (the timing between calving) can nearly double the current productivity of dairy animals.”

Another restraint, and ISET describes it as an “acute” one, is access to finance. It found that bank loan officers do not understand the agricultural SME market, most small farmers can’t write business plans and don’t have enough collateral to qualify for loans. Equally difficult are the workings of government support schemes, regulations, consumer protection, or the export opportunities under the EU’s Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA).

As ISET sees it: “There are many constraints association with the DCFTA and food safety regulations. The greatest challenge is the significant number of unregistered family farms that produce and sell milk and dairy products on a regular basis. According to Geostat, more than 97 per cent of milk in 2017 was produced by family farms. Furthermore, sector experts claim that up to 90 per cent of cheese is produced by unregistered households who sell their unlabelled produce (mostly cheese) at open markets through intermediaries.”

It took about eight years for ALCP to begin to achieve the changes being seen in dairy supply chains in regions in which it has been working and the development of the Georgian Milk Mark. Key was showing small farmers that it was more profitable in terms of time spent and cash not to make cheese but to become food safety complaint and just sell their raw milk through the Georgian Milk Mark system to larger certified dairy enterprises.

To do so they had to improve the quality of their milk and their hygiene standards, but education programs were run for them by the dairy enterprises, who in turn had been supported with capacity to do so by the ALCP program.

All the farmers interviewed (in a 2019 ALCP study) “increased their sales and profitability”. The dairy enterprises “also increased sales and profitability, most have diversified to include butter, cottage cheese, sour cream, ghee cheese with herbs, bottled milk”, says ALCP. What is more, those now in the new system include an increasing number of farmers and dairy enterprises who are “crowding in” having seen how profitable it has been for the original 3,000 ALCP-reached farmers and 39 enterprises.

A look at the Georgian Milk Mark website shows member dairy groups and their distributors, such as: Tsipora-samtskhe Ltd, which collects milk from 600-700 farmers, in Kakheti Tsivi’s Cheese which has 200-300 farmer suppliers, near Marneuli there is Tsintskaro and many others in various parts of the country.

The increase in farmer profitability has been substantial, says ALCP – from US$1.98 per capita per day at the start to US$6.42 in 2019. More than half of the workers are now working 40-hour weeks, new jobs are being created, and veterinary services upgraded and expanded. Now ISET has suggested a new target -more innovation in cheese products to help Georgia promote its “rich food heritage”, such as popular aged and less salty cheeses!

____________________________ ADVERTISEMENT ____________________________